|

A couple of weeks ago, I had the good fortune of spending two days in the city of light. Following professional as well as personal inclinations, I visited three exhibitions, which were strikingly different in size, organization, and ambition – different to such an extent, indeed, that only the chilly and surly demeanor of the porters at the entrance reminded me of their shared setting in Paris. In the following remarks, I would like to briefly reflect on these exhibitions so as to ponder the ways in which exhibitions shape our understanding of art, often in paradoxical ways.

The exhibition explores the many intersections between Toulouse-Lautrec’s work and that of his contemporaries. In the very first space, for instance, his work is compared to that of his teacher, Fernand Cormon, a historical painter. Seeing Cormon’s tableaux, the viewer is faced with a view of history that is marked not by the progress of civilization but by barbarity. This notion illuminates the art of Toulouse-Lautrec, in which supposedly civilized life is stripped of its veneer, so as to show the animality that lurks beneath. More recognizable points of reference, such as Degas and van Gogh, are present as well. Like these artists, Toulouse-Lautrec is one of the painters of modern urban life, and its seedy side in particular; his art has been pigeonholed as decadent or, less charitably, degenerate – a view that was reinforced by his physical disability and his bohemian lifestyle (at the exhibition, one learns that Toulouse-Lautrec sometimes stayed in brothels for weeks on end). As such, Toulouse-Lautrec’s work questions the distinction between high art (culture for the elite) and low art (culture for mass-consumption) that was so characteristic of his own time. On the one hand, his works did not result in financial gain, but were appreciated an bought by people belonging to his inner circle. On the other hand, he took ‘vulgar’ culture as his subject, which may lead one to infer that his works were meant as an appeal to popular taste. In other words, Toulouse-Lautrec tried to have his cake and eat it. Yet, in the long run, his approach was successful, as this exhibition shows: a huge portion of his work is now displayed in the Grand Palais, a cultural epicentre, in an exhibition that spans three floors. The exhibition is so vast that as one proceeds, one begins to believe that it will never end. The story that the exhibition tells, then, is different from the effect that it achieves: while the exhibition explores the local and particular qualities of this marginal artist, it at the same time sanctifies this art as being of universal and everlasting value. My own feeling, on leaving the exhibition, was that, perhaps, Toulouse-Lautrec’s work was too popular, too vulgar, and that this excessive vulgarity (which I here use in the qualitative and not the evaluative sense of the word) was what has made these works so prestigious in the long run.

In the case of The Alana Collection: Masterpieces of Italian Painting, however, I was lost. And this was unexpected, for there is a strong synergy between the exhibition and the museum’s permanent collection, which has a focus on medieaval and early modern works of art: an introductory film nicely highlights the many echoes that are thus created. No, I think I felt lost not because of my inability to understand the works in themselves, but because of their presentation. The exhibition’s title already points to nature of the problem: whereas in the case of Désirs & Volupté the name of the collector was willing to share his collection with the wider public was hidden in the text itself, in the case of The Alana Collection, their names were emphatically present. The exhibition is in many ways a tribute to their willingness to share their works with the wider public. The first room of the exhibition tries to replicate the benefactors’ living room, where their paintings vie for space. While the effort is an interesting one, its purpose is all too obvious, and the result makes it difficult to examine and scrutinize the actual works. Even more, the exhibition even features a rather hastily taken photograph of their living quarters, so that viewers can fully appreciate these works’ contemporary location.

As a result, the actual paintings get short shrift, even though these are magnificent. What the visitor remembers is the name of the collectors, but perhaps not in the way that the collectors envisioned. This is not meant as a jibe: without the efforts of private collectors such as Alvaro Saieh and Ana Guzmán, the art world would not be able to function in the way that it does, and it is their good right to ask that their willingness to share their passion with the world be acknowledged and recognized. What I want to highlight is another paradoxical effect: if one so openly asks for recognition, as in the present exhibition, the opposite effect is achieved. To be truly successful, an exhibition should let the collection speak for itself; only thus will the interested viewer fully appreciate the care that the collectors have taken, and be willing to recognize as benefactors, in the full sense of the word. I am aware of the irony that, of course, by addressing this issue, I have paid the collectors the compliment of talking about them rather than their collection.

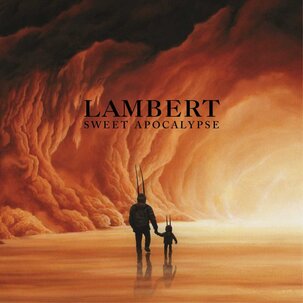

One particular surprise, for me, was the inclusion of John Martin’s The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (1822), which is the final painting, to be seen when one leaves the exhibition. I will readily confess that I did not know this work. Martin’s work has only quite recently been revalued: while his sublime historical tableaux were very popular in the early nineteenth century, his work was considered too dramatic and excessive for Victorian tastes. But it was not the innate qualities of this painting that struck me; nor was I reminded of the nineteenth-century preoccupation with antiquity, which is one of my own research interests. The first thing that came to mind – my mind, at least – was the album cover of ‘Sweet Apocalypse’, a beautiful collection of haunting melodies by the contemporary German pianist Lambert, who always performs while wearing a Sardinian mask. This album’s cover is a painting by Mioke and shows the musician walking with a child towards an eruption of light, whose source remains unknown (but given the album’s title, it appears most sinister).

There is of course a striking difference: whereas in Martin’s painting the citizens of Pompeii attempt to flee the apocalypse behind them, in Mioke’s painting two individuals calmly walk towards it. At the end of this wonderful exhibition in the musée du Luxembourg, then, with the crème-de-la-crème of British painting behind me, I saw an artwork by a (for me) unknown artist, which made me think of the painting of the cover of an album by a pianist who performs anonymously, but whose music thus, paradoxically, is reaching an ever-growing audience. Whether Lambert and Mioke are consciously referring to Martin’s painting, I cannot say; intertextuality may work in mysterious ways, as theorists such as Julia Kristeva and Roland Barthes have shown. What I can say, is that in our times anonymity may be a better guarantee for creating forms of imaginative engagement.

0 Comments

|

Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed