|

At the beginning of this month, the Radboud Young Academy hosted the very first serendipity session. Our aim was to see if and how we can foster more and more intense exchanges across the boundaries of faculties and research fields. Given that many more people attended than we had anticipated, this first attempt showed that interdisciplinary collaboration is not something that can be taken for granted. We organized this session around the topic of coffee. As a vital part of many workplaces, and not just the academic one, coffee plays an important role in our world; by looking at its history, at its impact on the brain, and at the language we use when we talk about it, we were able to arrive at insights that were as bracing as the coffee that we served (and which, admittedly, were just as attractive as the topic itself).

0 Comments

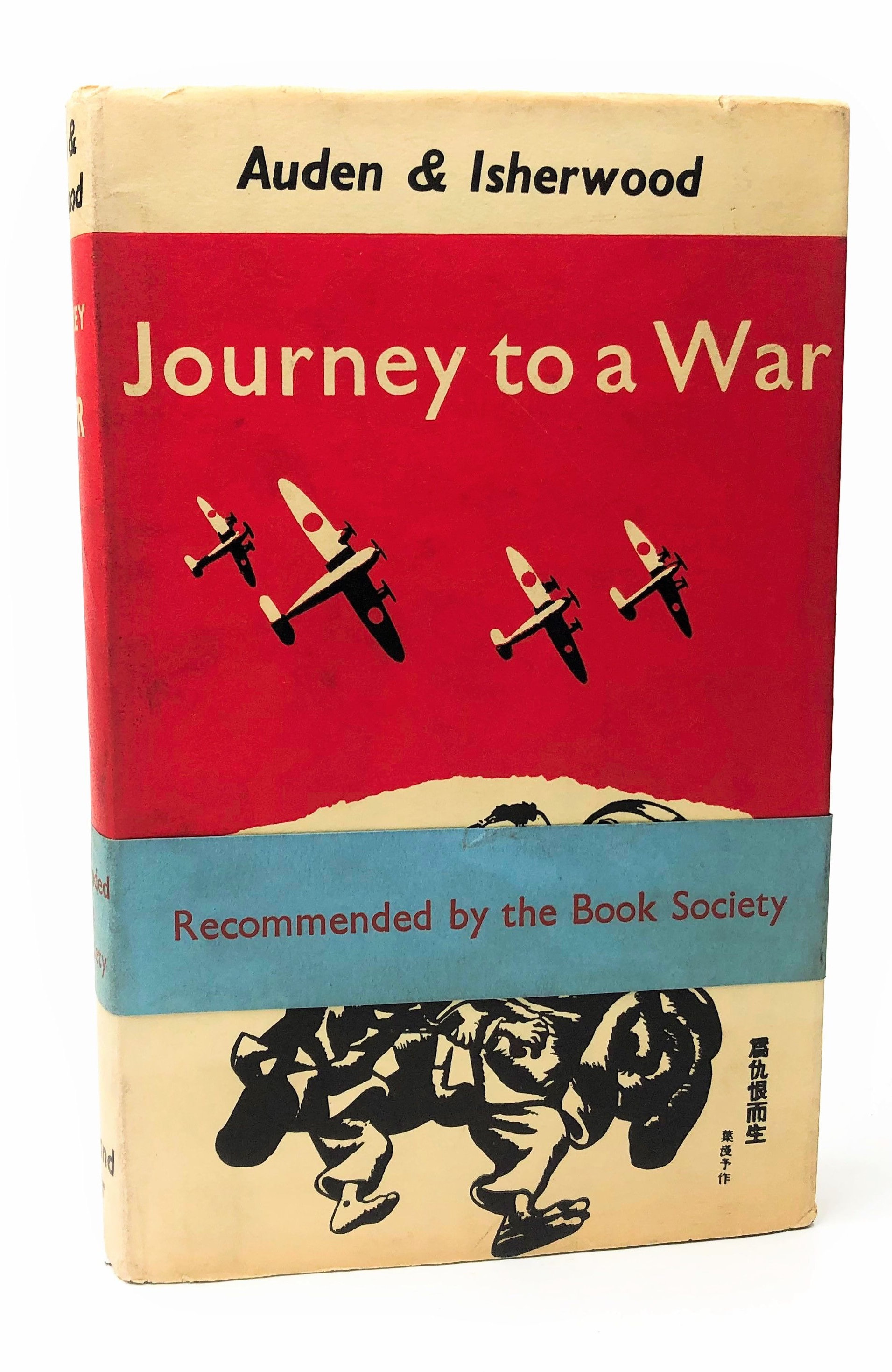

In two days' time, I will be leaving for a short research stay in Budapest. The primary goal is to visit particular sites and to explore a few libraries, with the aim of advancing my research into Hungarian literature and culture. As interlude, I will be traveling to Debrecen, in the East, where, wearing my hat as an anglicist, I will be talking about The Poetry of Trees, a particular book made by the British composer Thomas Pitfield in 1942.

Articles may take a long to mature, some more than others. One such article began 6 years ago, as a subplentary lecture at an ESSE conference, after which it was kept on the back-burner. When earlier this year the journal Languages Cultures Mediation published a CFP on cultural representation of and engagements with 'crisis', however, I was prompted to return to this text and to rethink my ideas. Like most of my recent work, the article itself deals with a geopolitical crisis: it examines how the Italian Risorgimento, which had a profound impact on the shape of English literature, did not leave a similar imprint on Irish literature. Even so, I was struck by the fact that a few Irish poets did address the Risorgimento and that in doing so they expressed a variety of positions (isolationism, catastrophism, liberalism, realism) that were informed by a complex constellation of geopolitical factors. In lieu of the abstract, I thought I'd post the introduction to this article (which can be found in its entirety here), because it illustrates how our own current geopolitical moment helped me find a new angle. The issue as a whole contains a variety of illuminating reflections the ways in which throughout history 'crisis' has played a role in different languages and cultures. After the end of the Cold War, certain thinkers and analysts began to harbour hope for the emergence of a post-national order, in which peace would be maintained through economic interdependence and international institutions. Francis Fukuyama famously maintained that “the world in which [people from the West] live is less and less the old one of geopolitics” and that “the rules and methods of the historical world are not appropriate to life in the post-historical one” (Fukuyama 1992, 283). The Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 is only the most recent reminder, however, that geopolitics, or the “influence of spatial environment on political imperatives” (Howard 1994, 132), remains of paramount importance. In one of the most-cited articles on the relationship between Russia and Ukraine, prompted by the annexation of Crimea in 2014, John Mearsheimer argues that Washington had been misguided in maintaining that the Kremlin would not interpret military actions near the Russian border as a geopolitical threat: "the two sides have been operating with different play books: Putin and his compatriots have been thinking and acting according to realist dictates, whereas their Western counterparts have been adhering to liberal ideas about international politics. The result is that the United States and its allies unknowingly provoked a major crisis over Ukraine" (2014, 84). Mearsheimer’s reliance on a contrast between liberal and realist approaches to foreign policy has been subjected to critique from various points of view (e.g., McFaul 2014, Sestanovich 2014). The role of literature and the arts in the formation as well as the response to this crisis deserves further scrutiny, however: like canaries in a coal-mine, cultural artefacts and activities may reveal aspects or perspectives that tend to remain under the radar in political analyses. The 2012 television adaptation of Mikhail Bulgakov’s The White Guard (1925), for instance, was inextricably bound to the annexation of Crimea: expanding on Bulgakov’s portrayal of revolutionary Kyiv in 1918, the series “portrays Ukraine as a hotbed of all sorts of revolutionary chaos and a place which already due to its geographical and cultural proximity poses a constant threat to the stable political order in Russia” (Zabirko 2019, 12). If anything, a consideration of such cultural interventions may help us situate geopolitical crises in their longue durée. To further explore the ways in which culture and geopolitics are mutually constitutive issues, this article examines how the nineteenth-century struggle for the unification of Italy, better known as the Risorgimento, left an imprint on Irish literature of the Victorian age. Although the nineteenth-century Risorgimento and the contemporary situation in Ukraine are vastly apart in space and time, a juxtaposition reveals some surprising continuities in the ways in which these international conflicts are framed. While today’s Western commentators tend to talk about the Ukrainian ‘crisis’, Victorian public moralists such as Matthew Arnold addressed the Italian ‘question’ (e.g., Bevington 1953). To call a geopolitical conflict a ‘question’ rather than a ‘crisis’ is to invoke a range of assumptions. As Holly Case has argued (2018), in the nineteenth century the genre of the ‘question’ developed into a mode of public discourse that was characterised by a tendency to interweave disparate issues: by bundling various questions, thinkers could present a solution that would solve different problems in one single stroke. This discourse had different outcomes: it cleared the road for the horror of the Final Solution, but it also contributed to the establishment of a liberal world order invested in the creation of international institutions that would safeguard and maintain global peace. The Second World War seemed to mark the demise of the ‘question’ as a way of addressing societal issues, in favour of the crisis paradigm. It is telling, however, that in twenty-first-century Russia the question discourse seems to have resurfaced along with the nineteenth-century notion of a Great Game between the different Great Powers. Given the possibility that we may be “on the cusp of another age of questions […] we might do well to consider what the first one wrought” (Case 2018, xv). A reconsideration of the Italian question from an Irish point of view is a rewarding case study. As recent research has shown, Irish literature was determined not just by its place within the United Kingdom, but also by geopolitical forces that operated on a larger, global level. By situating Irish poetry of the Victorian age in the context of the ‘Italian question’, I hope to complement ongoing investigations into the geopolitics of nineteenth-century Irish literature, and to thus subject the cultural mediation of geopolitical crises to further scrutiny. On Tuesday 7 June, the student association of the Arts and Culture Studies programme here in Nijmegen hosted a symposium on the relationship between art and pleasure. Invited to share a few thoughts, I thought I’d escape the confines of my home territory – literary studies – and talk about an art form that continues to exert a particular fascination, the art of videogames. It was a small step to translate these musings into a post for my department's celebrated blog, Culture Weekly.

While my reflections on videogames from the point of view of cultural theory may seem (and indeed are) a kind of spielerei, the subject of 'gamification' is want that warrants our attention, as gamification is infiltrating parts of reality, such as education, in ways that were unthinkable before the turn of the century. Using gamification in the classroom can work wonders for engagement, but does it come at too great a cost to deep thinking? For some answers to this big question, you might want to check out a piece I wrote for the Times Higher Eduction, which is follow-up of sorts to an earlier piece about the need for slow science.

A few weeks ago, I was invited to give a short presentation on my use of the adaptive learning platform Cerego. For two years now, I've been using this platform in my course on Text Analysis. This is a fairly theoretical course, in which students are confronted with a barrage of concepts and models in a short period of time. This platform turned out to be a useful scaffold, as it helps students memorise these concepts and theories, utilising a variety of forms (flashcards, fill-in-the-blank questions, short applications). In the first version, I mainly focused on the most important concepts and terms. When the advent of online and hybrid teaching hit us last year, I decided to go one step further and - rather than provide a recording of my lectures, as in many other courses - to use this system to creative an interactive handbook. The presentation can be viewed below.

It gives me great pleasure to announce that this subject will be featured in a forthcoming issue of the European Journal of English Studies, which I am putting together with my colleague Chris Louttit and Joanna Hofer-Robinson (University College Cork). This issue aims to push established scholarship on the ‘spatial turn’ in new directions through an examination of interstitial spaces, that is, the corridors, roads, and routes that exist in between and connect different spaces. While contributions on literary and cultural texts from any historical period are encouraged, the editors will particularly welcome proposals that deal with the long nineteenth century.

Topics might include but are not limited to:

Detailed proposals (up to 1,000 words) for essays of no more than 7,500 words and a short biographical blurb (up to 100 words) should be sent to all three editors by 30 November 2021: Frederik Van Dam, Joanna Hofer-Robinson, and Chris Louttit. This issue will be part of volume 27 (2023). All inquiries regarding this issue can be sent to the three guest editors. You can also find the CFP here and on the ESSE website. We’re hoping to have some kind of colloquium in the summer of 2022 in which all contributors (eight or thereabouts) can exchange reflections. A couple of months ago, I was invited to be part of the jury of the Nijmeegse Literatuurprijs 2020, together with Marijn Hogekamp and Heidi Koren. This literary prize was established to further the promotion and spread of literature in a part of the country that I now call home. We received more than fifty submissions, with many strong contenders. As someone who is used to assess scholarly work, I quite enjoyed the change of atmosphere. At the same time, I couldn't help but reflect on the activity in which I was participating, which has such an important place in the practice of cultural branding - as subject on which my colleagues in the the research unit SCARAB are publishing a book. You can read more about the prize on its website and hear me announce the winner on De Gelderlander.

Almost exactly a year ago, I published a review of Holly Case's The Age of Questions: Or, A First Attempt at an Aggregate History of the Eastern, Social, Woman, American, Jewish, Polish, Bullion, Tuberculosis, and Many Other Questions over the Nineteenth Century, and Beyond. In this fascinating study, Case examines the concept of 'the question' as a way of speaking and thinking about societal phenomena. The book has many merits, of which I would stress its real transnational perspective: the usual suspects from Victorian Britain appear alongside Hungarian diplomats (whom Case read in the original). While she focusses on the nineteenth century, the study prompts one to think beyond the turn of the century. I, for one, was reminded of how in King Ottokar's Sceptre, the eighth volume in the Adventures of Tintin, in which the Eastern Question and the Belgian Question are bundled and mirrored. The review was published in Karakter is now available for the general public here (in Dutch).

The long-awaited third part of my trilogy of classes on contemporary literature is now also available online. Both my appearance and voice show signs that the quarantaine (and teaching in the presence of two young children) is beginning to take its toll. But having made a start, I think it's better to soldier on. In this lecture, I discuss a second important movement, postmodernism. Postmodern narratives tend to question our experience of the reality in which we live. We can find manifestations of this tendency not only in philosophical prose such as W. G. Sebald's Austerlitz, but also in popular genres such as the adventures of Tintin or a computer games such as the Stanley Parable. In this lecture, we trace the emergence of these complex works to the acceleration of globalisation after WWII. |

Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed